From the 2021 issue of Endeavors.

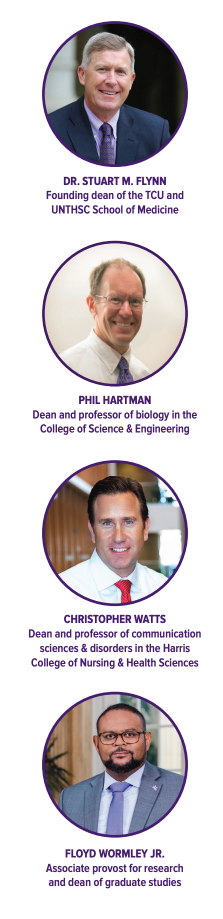

Dr. Stuart M. Flynn, founding dean of the TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine; Phil Hartman, dean and professor of biology in the College of Science & Engineering; Christopher Watts, Marilyn & Morgan Davies dean of the Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences; and Floyd Wormley Jr., associate provost for research and dean of graduate studies, discuss how student research could lead to significant impacts in all realms of health care.

What is the importance of research in training future health care practitioners?

Flynn: First of all, I think all of us should have the inquiry gene. I think physicians definitely should be inquisitive. Otherwise, you’re only as good as where you stopped asking the question, and that’s not where you want your physician to be. We’re very overt about that. We let students know before they come to our school that they will be asking a researchable question. If that makes them uneasy, then we’re just not the right medical school for them. The second thing is the issue of lifelong learning, which everyone talks about, but when you actually ask them, “Well, what does that mean?” it’s very hard to answer. I think this really helps me answer it: If you’ve actually asked the researchable question, you’ve designed your research protocol, you’ve done it, you have data and you interpret them, what you’ve just done is what you will spend the rest of your life reading that others have done in your discipline. You have both a feel for what that was like, and it also then allows you to have an element of how to critique it.

Watts: The cornerstone of clinical practice in health care is evidence-based practice. This is a requirement. It’s something that we train every student in the Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences in, and there are three components to evidence-based practice. One is the needs of the patient. What does the patient require? What does the patient want? The second is the experience and skills of the health care professional. How do the knowledge and skills they have align with those patient needs, what the patient wants, the outcome the patient wants? The third is research evidence. All three of these components are equal in value. Any decision that a health care professional makes should be based on the most current and strongest research evidence that validates the assessment that they’re going to do, the treatment they may give, the counseling they give to the patient. Research is critical to health care practice.

In the medical school in particular, students are required to have an ongoing research project from the start. Why is incorporating research throughout the pre-health programs such an imperative at TCU?

Flynn: When I arrived at Yale as a faculty member, they had this interesting graduation mandate of a four-year research thesis. I’d never heard of such a thing — medical school is busy enough as it is. Why would you impose that on everybody? A lot of us did research in medical school, but it wasn’t mandatory. As I settled in there, I started to see the immense value of that. I hosted a lot of medical students in my research lab, and I really became wedded to the tremendous value of what these students were getting. [Other] medical schools might mandate a month of research between the first and second year, and students have to get up in front of their classmates and give a presentation. That’s fantastic. But that’s not what we do. We actually run the marathon with the four-year research thesis; we don’t run the hundred-yard sprint. But I’m wedded to this. That’s why when I came here, we set this up, and the downstream value will be just invaluable to our graduates.

Hartman: In the College of Science & Engineering, we have a significant number, maybe 40 percent of our undergraduates, do research in a substantive sort of way, much higher than at most institutions. Usually when people do research, particularly at the undergraduate and medical school level, they tend to be widgets. They go in and do a very fine, very narrow, very prescribed sort of thing where, frankly, you don’t need a high level of intelligence to do it. So the inquiry, the natural curiosity that Stuart spoke of, you don’t really need that in many undergraduate research opportunities. I’ve spoken with individuals who really had no idea what they were doing, saying, “I pipette solution A into tube B.” It’s very different at TCU. The medical school has the scholarly thesis as the capstone in that experience. In the College of Science & Engineering, we are assigning students a specific project. Again, there’s the need for them to understand the literature. It’s a much more comprehensive experience. And it speaks to that element of curiosity.

Watts: For graduate nursing there is a research requirement, and undergraduate nurses have the choice to have a more in-depth research experience with a faculty member as part of their curriculum. There are dozens of nursing students who go beyond what’s in the curriculum requirements for research training. They do a mentored research project with a faculty member, and every year we highlight these at a college research symposium for students where we have poster presentations and some talks. We’ve had hundreds of students each year participate in this. Students from the get-go are so engaged and connected with research and how research is tied to health care that it’s just part of their being, and they’re able to speak the language of science as well. It applies to what they’re learning in their health care trade.

What does a teacher-scholar model look like, and why is it important for a student to see that faculty are active in research?

Hartman: My bread-and-butter course between 1981 and 2012 was a junior-senior level genetics class. When I gave my last lecture, probably 80 percent of the material I talked about that semester had not been discovered in 1981. If I wasn’t keeping up on the field, truly keeping up, and if my degree of keeping up was to read textbooks, I would have quickly devolved into a mediocre, if not worse teacher. We simply have to be current in our disciplines. We have to attend meetings, we have to understand where science is now. And the best way to do that is to do science. I think the best teachers are actually those who are engaged scholars. They complement one another.

Flynn: Can I be a good clinician for the next 30 or 40 years after I graduated and finished my residency? The answer is yes. Am I maybe on some kind of curve of falling behind the state of the art? The answer is probably yes, no matter how much I read. However, if I’m also doing any kind of investigative work, that entails expanding my reading. If I’m going to publish, I have to be on top of my references, I have to be able to defend what they’re saying and I’m valuing them. It’s because they have that inquisitive gene, which is exactly what we’re trying to both discover when you come here and then grow as you are here.

Wormley: It takes a lot of time to take a green undergraduate student and teach them how to do the research in a lab. The investment in our students is an investment in their lives. I see this as generational because what we do for our students helps lift them and their families and our community. When you’re training professionals, you’re training colleagues, you’re giving back to academia. One of the responsibilities that we have being in academia is that we keep it going, that we create a pedigree of individuals. I know of some individuals who’ve been in science for years, but we look back at who they trained: Do they have anybody still doing research? It’s almost seen as a failure if they don’t versus looking back and seeing a legacy. We are preparing our students with the practical hands-on knowledge and experience to be able to make the best and current health care decisions, to provide the best service to their patients and to always be lifelong learners. In this pandemic, we’ve leaned on our health care providers, we’ve leaned on our scientists, we’ve leaned on these people to come up with therapeutics, vaccines and medicines to get us through something that we’ve never seen before. Those who have been trained properly notice what changes make the patient better. They’re evaluating and they’re making on-the-spot changes that actually save lives. The ability to train people to critically think and evaluate in the moment saves lives. What we do here is prepare people to be able to critically think, evaluate and make decisions that save lives.

How is TCU helping to transform the future of health care delivery?

Hartman: In the College of Science & Engineering, we’re doing it two ways. One is we’re making relatively small but discrete contributions to our body of knowledge — that’s the pure scholarship. But I think more important than that, we are training students who are going to go on to careers in the health care professions.

Flynn: It’s absolutely what we covet. It’s a little bit multidimensional. The dimension within the medical school is to train students who are inquisitive. That’s No. 1. I think virtually everybody who graduates from medical school nationwide has a grasp of medical knowledge. That’s the baseline. The part that the patients find really missing isn’t a question of if their physician has that baseline. What they struggle the most with is the lack of listening and the lack of communication. Now that sounds really trite. A lot of doctors at other medical schools roll their eyes and ask why that’s such a big deal. If you talk to the patients, you very quickly realize why that’s such a big deal. It’s a relatively simple adjustment. It’s huge to the patient-physician interaction. So we talk about transforming health care: It starts with that interaction. What we will do in Tarrant County — it’s already happening — is we now become a magnet for our clinical partners to recruit and hire a different kind of physician. They can hire a cardiovascular surgeon who is asking, “How do I become a part of this medical school?” That’s a big deal. That means they care enough to want to be a part of this and they know what that means because they trained in that environment. The transformation starts: You have a different kind of physician workforce in our community. It is changing under my eyes. Developing residency programs in our community changes the doctors and how they practice and that system. It changes the attraction to bring doctors into that system who like to train residents. At the end of this pipeline those hospitals are going to hire some of these trainees. It doesn’t happen overnight. You change it one step at a time.

— Trisha Spence

Editor’s Note: The questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.